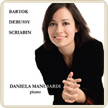

| DANIELA MANUSARDI

Daniela Manusardi,

concertista di pianoforte e compositrice, ha iniziato fin da giovanissima

gli studi di pianoforte e composizione presso il Conservatorio “G.Verdi”

di Milano, dove si è diplomata a pieni voti in pianoforte

nel 1999 sotto la guida del Maestro Annibale Rebaudengo e, successivamente,

in Composizione nella classe del Maestro Mario Garuti.

Dal 1999 al 2002 ha proseguito il suo perfezionamento pianistico

con Carlo Levi Minzi. Nel 2002 è stata ammessa alla prestigiosa

Accademia Musicale Statale di Trossingen in Germania, dove ha conseguito

con il massimo dei voti la Laurea di Secondo Livello in pianoforte

e sta ultimando il Solistische Ausbildung nella classe del Prof.

Tomislav Baynov, e la Laurea di Secondo Livello in Klavier-Kammermusik

nella classe del Prof. Akos Hernàdi.

Ha arricchito la sua formazione con Masterclass tenute da importanti

figure del pianismo internazionale quali Rudolf Kehrer, Livia Rév,

Karl-Heinz Kaemmerling, e Johann Van Beek.

Considerata come un “brillante esponente del contemporaneo

concertismo classico“ (Maurizio Franco) svolge attività

concertistica dal 1994 sia in veste di solista, sia in gruppi di

musica da camera (è membro del tedesco “Baynov-Piano-Ensemble“,

che nel 2007 è stato incluso insieme ad artisti come Martha

Argerich e Arcadi Volodos nel prestigioso CD “ The Symphonic

Steinway “) nell’ ambito di numerosi festival internazionali,

come il “41°Festival internazionale di musica da camera

di Cervo 2004” e il “44° Festival internazionale

di musica da camera di Cervo 2007”, Festivals Dino Ciani,

Festival e concerti della Valtidone, Steinway Musiktage Festival

e Bechstein Festival in Germania, “14° Stagione Atelier

Musicale” alla Palazzina Liberty di Milano, “ Festival

Zilele muzicale Targumuresene ” presso la sala grande della

Filarmonica di Stato di Targu Mures, in Romania e altri, in Europa,

riscuotendo vivo successo di pubblico e di critica.

Il suo repertorio spazia da Bach sino agli autori contemporanei,

con una particolare predilezione per la letteratura musicale del

primo Novecento europeo; Daniela Manusardi è nota al pubblico

per le sue interpretazioni di autori come Debussy, Ravel, Bartòk,

Schoenberg, Berg, Rachmaninov, Scriabin.

Ha effettuato registrazioni discografiche radiotelevisive in Italia

e in Svizzera per la “Radio Televisione della Svizzera Italiana”,

Limenmusic.

Daniela

Manusardi is a pianist and a composer. She was first taught piano

and composition at the Conservatorio “G. Verdi” in Milan,

where she obtained her piano degree in 1999 and her composition

degree in 2005. After her degree, she specialized with Carlo Levi

Minzi. In 2002 she was admitted at the Trossingen Music High School

(Germany), where she obtained her piano Master - degree in 2004.

Since 2006 she has been specializing as a soloist with Tomislav

Baynov and in chamber music with Akos Hernádi.

She also took part at several master-classes with world-famous pianists,

like Rudolf Kehrer (a pupil of Heinrich Neuhaus’), Karl-Heinz

Kaemmerling, Livia Rev, und Johann Van Beek.

Daniela Manusardi was defined a “brilliant classical pianist”.

She has been giving concerts since 1994, both as a soloist and as

a member of chamber music groups. She is a member of the Baynov

Piano Ensemble. She took part at different national and international

music festivals, such as the 41st and the 44th Cervo international

chamber music festival, the Valtidone festivals, the Dino Ciani

festival, the Ascoli Piceno festival, the “Steinway Musiktage”,

the Bachstein festival, the 14th concert season of the Atelier Musicale

in Milan, the Neumarkt international music festival and many others,

both in Italy and in Germany, Switzerland, Rumania.

Among Daniela Manusardi’s manifold activities there are also

radio- and video-recording in Italy and Switzerland, Limenmusic.

Daniela

Manusardi, Pianistin und Komponistin, erhielt ihren ersten Klavier-

und Kompositionsunterricht am Conservatorio „G. Verdi“

in Mailand; dort hat sie 1999 ihren Klavierabschluss unter der Leitung

von Annibale Rebaudengo mit der Bestnote und 2005 den Kompositionsabschluss

unter der Leitung von Mario Garuti erlangt.

1999 bis 2002 hat sie sich unter der Leitung von Carlo Levi Minzi

im Fach Klavier fortgebildet. 2002 wurde sie an der Staatlichen

Hochschule für Musik Trossingen aufgenommen; hier machte sie

2004 ihren Abschluss im Fach Klavier (Künstlerische Ausbildung).

Zurzeit studiert sie an dieser Musikhochschule weiter im Fach Solistische

Ausbildung (Klavier) unter der Leitung von Tomislav Baynov und im

Fach Klavier-Kammermusik unter der Leitung von Akos Hernàdi.

Sie nahm an mehreren Masterclasses mit weltberühmten Pianisten

wie Rudolf Kehrer, Karl-Heinz Kaemmerling, Livia Rev und Johann

Van Beek teil.

Daniela Manusardi gilt als „brillante klassische Konzertmeisterin“

(Maurizio Franco, Musica Oggi): Sie tritt seit 1994 als Solistin

und in Kammergruppen auf. Sie ist festes Mitglied des Baynov-Piano-Ensembles.

Sie nahm an mehreren nationalen und internationalen Festivals teil,

etwa am 41. und am 44. Internationalen Kammermusikfestival in Cervo,

an den Festivals und Konzerten der Valtidone (Italien), am Dino-Ciani-Festival,

am Ascoli-Piceno-Festival, an den Stenway-Musiktagen, am Bechstein-Festival,

an der 14. Konzertreihe des Atelier Musicale (Mailand), am Neumarkter

Internationalen Musikfestival und vielen anderen in Italien, Deutschland,

Rumänien und der Schweiz.

Ihr Repertoire erstreckt sich von Bach bis heute, mit besonderer

Vorliebe für die musikalische Produktion Anfang des 20. Jahrhunderts.

Zur musikalischen Tätigkeit von Daniela Manusardi zählen

Rundfunk- und Fernsehaufnahmen in Italien und der Schweiz für

den Rundfunk der Italienischen Schweiz,Limenmusic.

OLTRE IL NOVECENTO

UN VIAGGIO INTORNO AL PIANO

A

guardarlo bene, soprattutto nella versione gran coda, il pianoforte

sembra davvero un vascello su cui imbarcarsi per viaggi avventurosi,

e Liszt, in un suo articolo del 1837 sulla Gazette Musicale, dichiarava

che ‘il pianoforte è per me ciò che la nave

è per il marinaio e il cavallo per l’arabo’.

L’Ottocento era stato un secolo di grandi viaggi, tanto per

avventura quanto per conquista coloniale, ma alla fine del secolo,

grazie anche alle Esposizioni Universali, le culture ‘altre’

compivano il viaggio in senso inverso per conquistare gli spiriti

più attenti del mondo occidentale; così nel 1889,

a Parigi, un gruppo di suonatori balinesi colpì profondamente

la fantasia del giovane Debussy, che dal loro esempio ricevette

lo stimolo per ripensare la musica su basi nuove.

Stavolta però il pianoforte divenne non un mezzo per incantare

o stupefare il pubblico, ma una sonda per perlustrare gli abissi

della musica: Debussy, dopo aver estratto dallo strumento tutti

i colori più fantasiosi e le più seducenti preziosità

armoniche, alla fine della vita e della carriera rielabora il suo

stile svelando inaspettate consonanze col mondo musicalmente più

estremo che lo circonda.

Il secondo libro dei Preludi è pubblicato nel 1913, e il

29 maggio dello stesso anno Igor Stravinsky aveva gettato il suo

guanto di sfida nell’arena con La Sagra della Primavera, ma

l’anno prima, il 9 luglio a Bellevue, Stravinsky e Debussy

avevano eseguito il balletto in una trascrizione a quattro mani

(al termine i due erano troppo emozionati per parlare, dopo tanta

e tale musica). Facile pensare che il francese, da sempre onnivoro

raccoglitore di suggestioni, fosse rimasto impressionato dall’incredibile

capacità organizzativa del russo, in grado di ricavare le

più audaci tessiture dalla scomposizione di ‘normali’

accordi sovrapposti.

Debussy molto spesso si comporta in quest’opera come il giocatore

di scacchi che si diverte a creare sulla scacchiera i più

complicati problemi col minimo indispensabile di pezzi, a volte

anzi cacciandosi di proposito in un vicolo cieco per mettere alla

prova la sua capacità di districarsi. A volte il gioco è

scoperto, come in Les Tierces Alternèes, con quell’inesausto

rincorrersi della semplice formula armonica in tutti i registri

della tastiera, altre volte invece è più velato, come

in Canopes, quasi una rievocazione delle Danseuses des Delphes ma

coi profani fuori dal tempio, perché questo rito lo possono

seguire solo le anime purificate dal fuoco sacro.

Ma il viaggio musicale in questi preludi pare allo stesso tempo

prendere congedo dal passato, con le Bruyeres care ai pittori impressionisti

e la Ondine flessuosa entrambi rielaborati in un clima fuori dal

tempo e dalla moda, e preannunciare il futuro: così il General

Lavine-Eccentric segna l’ingresso trionfale della musica circense

nella quale sguazzerà il Gruppo dei Sei del dopoguerra- anche

se il solito pre-minimalista Satie si aggira già nei paraggi

meditando l’irriverente balletto Parade di tre anni dopo-,

l’omaggio al dickensiano Pickwick si traduce in una ghignante

satira, come se ‘Claude de France’, per dirla con D’Annunzio,

volesse vendicare musicalmente Giovanna d’Arco, e così

via in un procedere insieme rigoroso e libero che trova anche una

sorta di corrispondenza speculare inversa fra i brani, col primo

che replica al dodicesimo e così via.

Non casualmente, i due preludi che aprono e chiudono il libro guardano

nello stesso tempo al passato e al futuro: Brouillards evoca le

atmosfere di fine Ottocento ma Feux d’Artifice le distrugge

e rinnega attraverso passi quasi rumoristici come all’inizio,

con puntute seconde minori e glissando che paiono voler varcare

in un sol colpo la linea di confine tra suono e rumore.

Quasi per misteriosa congiunzione astrale, il 12 marzo dello stesso

1912 in cui Debussy suonava la Sagra con Stravinsky, un appena quindicenne

Henry Cowell presentava al San Francisco Music Club vari brani di

sua composizione dai titoli sconcertanti- Night Sounds, The Ghouls

Gallop, Weird Nights, ad esempio- cui corrispondevano suoni altrettanto

sconcertanti, fatti di pugni e avambracci sulla tastiera, i noti

tone clusters, e di esecuzione sulla cordiera, mentre sulla costa

orientale Charles Ives stava lavorando alla sua celebre Concord

Sonata, pubblicata nel 1914.

Sembra proprio che tutti questi geni usassero nello stesso momento

il pianoforte come moderni alchimisti, per cavarne effetti e tessiture

fino ad allora ignorati o cancellati dalla cultura ufficiale.

Bartòk,

dal canto suo, aveva lavorato con le armi dell’etnomusicologo

per nobilitare quell’ aspetto della cultura ungherese fortemente

connotato. I viaggi di ricerca gli avevano svelato una cultura ancora

tutta da esplorare, con quelle peculiarità melodico-armoniche

adattissime a fungere da munizione per la propria personale visione.

Bartòk dimostra proprio nelle Improvvisazioni su canti popolari

ungheresi (del 1920) nelle quali torna, ora citato ora quintessenziato,

lo stilema lisztiano che consiste nel prendere una melodia famosa

e riprodurla circondandola di ghirlande di note, arpeggi e fioriture,

fatto particolarmente chiaro nelle parafrasi da opere come quella

notissima sul verdiano Rigoletto. Qui invece il predetto stilema

viene ricomposto da una diversa prospettiva con effetto dirompente,

e viene mutato di senso grazie ad una scrittura angolosa, antisentimentale

e antiretorica, dove- come avviene nel quinto pezzo- le seconde

minori che avevano stuzzicato Debussy deflagrano allo scoperto alternandosi

con quinte perfette evocative della musica rurale, o dove nel settimo

pezzo, non a caso scelto come omaggio a Debussy per un numero commemorativo

della Revue Musicale, in cui il tema popolare veleggia fra tessuti

sonori memori della Cathédrale Engloutie ma spogliati di

qualunque suggestione vaporosa.

La Grande Guerra aveva definitivamente ucciso il mondo di Melisenda

e delle monetiane ninfee, e se il musicista francese era morto durante

l’ultima più cruenta fase, il suo collega ungherese

si era sobbarcato il difficile incarico di salvare quanto era possibile

della propria cultura per farne omaggio al mondo intero, senza mai

chiudersi in un folklorismo di maniera da salotto buono piccoloborghese,

bensì cercando sempre nuove suggestioni sonore ai confini

del rumoristico, tanto che cinque anni dopo chiese proprio a Cowell

il permesso di usare i tone clusters in alcune sue composizioni.

Nel

mondo della Belle Epoque che andava a passo di danza verso il proprio

suicidio pareva fuori posto uno come Scriabin, molto meno a suo

agio del compagno di studi Rachmaninov in un ambito ancora ‘salottiero’

che si beava di virtuosismi pianistici ed esotismi compositivi,

e insieme molto più moderno nel suo flirtare con la teosofia,

nel suo immaginare sinestesie musicali e visive con una commistione

di elementi- suoni, colori, danze, proiezioni e quant’altro-

che anticipa la attuale contaminazione postmoderna di almeno sette

decenni.

Anche lui liquida il pianismo di tipo romantico o tardo-romantico

che si era via via impoverito, ma lo fa con una procedura carica

di gogoliana ironia: il Preludio e Notturno per la sola mano sinistra

si incaricano di ricostruire un mondo tutto tramato di languidi

arpeggi, dolci melodie e sommessi accompagnamenti, i quali però,

se eseguiti normalmente dalle due mani, potrebbero risultare quasi

scontati. Scriabin, affida tutta la scrittura musicale ad una sola

mano, seppur con tutte le difficoltà tecniche del caso, e

conferisce al brano un senso di pienezza e corposità sonora

rara, carica di tutte le nuances armoniche necessarie per esaltare

la linea melodica.

Il

viaggio, naturalmente, continuerà prevedendo come tappe il

pianoforte preparato di John Cage, il well tuned piano di La Monte

Young, la straziante ed impossibile riproposta di mondi musicali

perduti fatta da John Adams, oppure nell’ambito jazzistico

l’africanità incrociata con la modernità del

super virtuoso afro-americano Cecil Taylor, insieme diplomato al

conservatorio e studioso di musica africana, ma tutto è partito

da qui, da questa volontà di prendere il pianoforte nella

sua accezione di mobile destinato ad aumentare il prestigio di chi

lo possiede e/o lo suona per trasformarlo in laboratorio continuo

di invenzioni e scoperte cariche di passato e insieme gravide di

futuro.

Francesco

Chiari

BEYOND

THE 20TH CENTURY

A JOURNEY AROUND THE PIANO

If

you take a closer look at it, especially the ‘Grand’

variety, the piano does look like a vessel to sail on for adventure-packed

journeys; Liszt himself, in an 1837 article for the Gazette Musicale,

stated: ‘The piano is for me what the ship is for the sailor

or the steed for the Arab’.

The 19th century had been a century of world-wide travels, both

for spirit of adventure and for colonial conquest, but at the end

of the century – courtesy of Universal Exhibitions –

‘different’ cultures travelled the opposite way to conquer

the most attentive spirits in the Western world. In 1889 Paris a

group of Balinese players set fire to young Debussy’s fantasy,

who took after their example to reinvent music almost from scratch.

This time, the piano wasn’t a medium to cast a spell on an

audience or leave them goggle-eyed, but a sound to fathom musical

abysses. Debussy – after having spent a lifetime evoking from

his instrument the most imaginative colours and the most charming

harmonic jewels – at the very end of his life and his career

reshapes his style, unveiling surprising consonances with the most

radical music around him.

The second book of Préludes was published in 1913, the very

year Stravinsky on May 29th threw his gauntlet with The Rite of

Spring; the year before, at Bellevue, on May 9th, Stravinsky and

Debussy had played the ballet in a piano duet transcription (at

the end both of them, overwhelmed by such music, were unable to

speak). It’s easy to assume that Debussy, as usual a tireless

collector of hints, was impressed by his Russian counterpart’s

incredible compositional skill, which enabled him to extract the

most daring textures from ‘ordinary’ superimposed chords.

Several times in this work we find Debussy behaving like a chess

master who takes great pride and joy in creating on the chessboard

the most intricate problems with a minimum of pieces, sometimes

even painting himself into a corner to test his skilfulness in sorting

out that tricky situation (Houdini who ties his wrists all by himself).

Sometimes we can see what he’s conjuring up, like in Les Tierces

Alternées, with that simple harmonic formula playing hide-and-seek

all over the keyboard, but other times it’s more difficult

to see through, like in Canope, which fondly recalls Danseuses de

Delphes but this time with laity outside the temple, for only who

passed through the sacred fire can witness this rite.

The musical journey in these Préludes seems to take leave

from the past, with the Bruyères beloved by Impressionists

painters and the supple Ondine, who look like inhabitants of a world

beyond time and fashion, and at the same time to foresee the future:

General Lavine – eccentric triumphantly heralds circus music,

in which after the Great War Le Six will wallow – although

the pre-minimalist Satie was already hovering around the block,

mentally planning the iconoclastic ballet Parade which was created

three years later; the homage to the Dickensian character Pickwick

turns out to be a sneering satire of British hypocrisy, as if ‘Claude

de France’ (to quote D’Annunzio) wanted to avenge Joan

of Arc, and so on and so forth with a musical process at once stern

and free, in which we even find a sort of mirror-reflection between

these preludes, the first mirroring the twelve etc.

It is not by chance that the opening and closing preludes look simultaneously

backward and forward: Brouillards evokes late 19th century atmospheres,

but Feux d’Artifice destroys and denies them with almost rumbling

passages like the one at the beginning, where spiky minor seconds

and glissandos seem to cross in one fell swoop the line between

sound and noise.

As in a mysterious astral conjunction, on March 12th of that year

1912 in which Debussy played the Rite with Stravinsky, a 15-years-old

Henry Cowell introduced at San Francisco Music Club several of his

own pieces, whose disquieting titles – Night Sounds, The Ghouls

Gallop, Weird Nights – were matched by disquieting sounds,

with fists and forearms on the keyboard (the notorious tone clusters)

and plucking of strings inside piano; at the same time, on the East

Coast Charles Ives was working on his famous Concord Sonata for

piano, published in 1914.

Bartók,

in his own peculiar way, used ethnomusicologist’s tools: he

travelled by and large his country – Hungary – and came

across a cultural world which still waited for being explored. The

composer profitably took inspiration from those melodic and harmonic

peculiarities, as he demonstrates in his Improvisations on Hungarian

peasant songs (1920). There we can find again, either quoted or

evoked, the Lisztian pattern of playing a well-known melody with

a flourishing array of garlands of notes, arpeggios and embellishments,

as we can see very clearly in Liszt’s operatic paraphrases

like the very famous one on Verdi’s Rigoletto. Bartók,

on the contrary, reshapes the aforementioned stylistic pattern from

a different angle with devastating effect, thanks to a spiky, anti-sentimental

and anti-rhetoric way of writing through which nothing seems the

same: in the fifth improvisation, those minor seconds which tickled

Debussy’s fantasy now burst out, alternating with open fifths

redolent of folk music, while in the seventh one – not surprisingly

chosen as a homage to Debussy in a special issue of the Revue Musicale

– the peasant’s theme sails through sonic landscapes

reminding us of the Cathédrale Engloutie, but without any

dreamy suggestion.

The First World War definitely destroyed the world of Mélisande

and Monet’s water-lilies, and if the French musician died

during the war’s final, harshest phase, his Hungarian colleague

took upon himself the forbidding task to save everything was possible

of his own culture to make it known to the whole world: therefore

he never secluded himself in a bogus folkloric style good enough

for petit bourgeois parlours, but always searched for new sonic

combinations, so much so that five years later he even asked Henry

Cowell for the permission to use tone clusters in his own compositions.

The

Belle Epoque which danced while sinking down seemed to have no room

for someone like Scriabin, who was much less at ease than his schoolmate

Rachmaninov in a musical environment still geared to a ‘salon’

music garnished with flashy piano virtuosities and exotic reminiscences,

and at the same time much more modern by flirting with theosophy

and conceiving musical and visual synesthesias whose medley of various

elements- sounds, colours, dances, projections and the like- anticipates

post-modernism by almost seven decades.

He too disposes of that Romantic and Late Romantic piano style which

had gradually fallen on hard times, but he does it with almost Gogolian

irony. Its Prelude and Nocturne for left hand only take care to

recreate a simpering world of waving arpeggios, sweet melodies and

subdued accompaniments, which anyway, if played by both hands, could

appear phoney and trite. By shouldering the whole musical burden

on one hand, the link one, and in spite of inevitable technical

difficulties, in this piece Scriabin attains a full sound and a

musical density containing all harmonic nuances required to emphasize

the melodic line.

Of

course, the journey will not stop and among its stages we will find

Cage’s prepared piano, La Monte Young’s well tuned piano,

John Adams’s heartrending and impossible unearthing of lost

musical worlds, not to mention in jazz field the cross-breeding

of Africanism and Modernism in the style of the African-American

pianist Cecil Taylor – who is graduated at the Academy of

Music, though. Everything, however, started here, from this will

to take the piano as a piece of furniture which greatly increases

the owner’s prestige and turn it into a perennial workshop

of inventions precariously balanced between past and future.

Francesco

Chiari

Jenseits des 20. Jahrhunderts

Eine Reise ums Klavier

Beim

genaueren Hinsehen sieht ein Klavier, und besonders ein Flügel,

tatsächlich aus wie ein Schiff, mit dem man nach abenteuerlichen

Reisezielen losfahren kann. Selbst Liszt erklärte in einem

von ihm 1837 für die Gazette Musicale verfassten Artikel: „Das

Klavier ist für mich, was für den Seemann das Schiff und

das Pferd für den Araber ist.“

Im 19. Jahrhunderte hatten mehrere Überseereisen zum Zweck

der Eroberung und Kolonialisierung ferner Länder und Kulturen

stattgefunden, doch unternahmen diese ‚anderen’ Kulturen

um die Jahrhundertswende eine Rückreise und eroberten die aufmerksamsten

Geister des Abendlands. Zum Beispiel wurde Debussy 1889 in Paris

von einer Gruppe balinesischer Spieler so tief beeindruckt, dass

er einen neuen Impuls bekam, um seine Musik auf einer grundsätzlich

neuen Basis zu gründen.

Diesmal diente das Klavier jedoch nicht dazu, das Publikum zu bezaubern

bzw. zu erstaunen, sondern, wie ein Lot, zur Erforschung musikalischer

Tiefen. Debussy hatte die fantasievollste Kolorite sowie die kostbarsten

und verführerischsten Harmonien aus dem Klavier gewinnen können.

Jetzt, am Ende seines Lebens und seiner Karriere, modifiziert er

seinen Stil und zeigt unerwartete Ähnlichkeiten mit der musikalisch

extremeren Welt, die ihn umgibt. Der zweite Band des Préludes

wird 1913 veröffentlicht; am 29. Mai desselben Jahres hatte

Igor Strawinski mit der Frühlingsweihe der herkömmlichen

Musik den Fehdehandschuh hingeworfen. Eigentlich hatten Strawinski

und Debussy bereits ein Jahr davor am 9. Juli das Ballett in einer

Transkription für Klavier zu vier Händen in Bellevue aufgeführt.

(Danach waren die beiden in Anbetracht solch aufregender Musik viel

zu betroffen, um auch nur ein Wort aussprechen zu können).

Mann kann sich leicht denken, dass der Franzose – seit jeher

ein penibler Sammler externer Anregungen – von der unglaublichen

Kompositionsfähigkeit des Russen beeindruckt worden war: Dieser

hatte aus ‚gewöhnlichen’, überlagerten Akkorden

verwegene Klangtexturen zu gewinnen gewusst.

Im zweiten Band der Préludes geht Debussy oft vor wie ein

vergnügtes Schachspieler, der die schwierigsten Positionen

mit wenigen Stücken auf dem Schachbrett kreiert und manchmal

bewusst in eine Sackgasse gerät, um sein Geschick, sich herauszuwinden,

zu erproben. Manchmal spielt er mit offenen Karten, wie in Les tierces

alternées, wo eine einfache harmonische Formel über

die Tastatur hin und her gleitet; manchmal ist sein Spiel nicht

so leicht überschaubar, wie in Canope, das an Danseuses de

Delphes erinnert; diesmal bleiben jedoch die Laien außerhalb

des Tempels, denn nur eingeweihte Seelen dürfen am Ritus teilnehmen.

Auf der musikalischen Reise der Préludes wird Abschied von

der Vergangenheit genommen, etwa in den von den Impressionisten

geliebten Bruyères oder in der geschmeidigen Ondine –

beide gelten als Kompositionen außerhalb des damaligen Zeitgeistes.

Zugleich wird die Zukunft begrüßt: Das Stück General

Lavine – eccentric kündigt der triumphierende Eintritt

der Zirkusmusik an; darin wird sich in der Nachkriegszeit die Gruppe

der Sechs wie in ihrem Element fühlen, obwohl der vor-minimalistische

Satie bereits tätig war und sein freches Ballett Parade in

seinem Geist plante, das er drei Jahre später vorführen

würde. Außerdem verwandelt sich Debussys Hommage auf

den Dickens’schen Mr. Pickwick in eine hämische Satire

britischer Heuchelei, als wollte ‚Claude de France’

– um D’Annunzio zu zitieren – Jeanne d’Arc

musikalisch rächen. So geht Debussy also vor, rigoros und doch

frei: Die zwölf Stücke spiegeln sich in umgekehrter Reihenfolge

ineinander wider – das erste im zwölften und so fort.

Nicht zufällig blicken die beiden Préludes, die den

Band eröffnen und schließen, gleich nach hinten und nach

vorne. Brouillards evoziert die Stimmung um die Jahrhundertswende,

Feux d’Artifice zerstört und verleugnet sie durch fast

rumpelnde Passagen, wie die am Anfang auftretenden kleinen Sekunden

und Glissandos zeigen, die an der Grenze zwischen Klang und Geräusch

liegen.

Das muss eine geheimnisvolle Sternenkonjunktur bewirkt haben: Am

12. März 1912 – im selben Jahr, in dem Debussy die Frühlingsweihe

mit Strawinski spielte – führte ein kaum fünfzehnjähriger

Henry Cowell beim San Francisco Music Club diverse selbstkomponierte

Stücke auf, die verblüffende Titel trugen, etwa Night

Sounds, The Ghouls Gallop, Weird Nights. Diesen Titeln entsprachen

ebenso verblüffende Klänge, die aus Fausten- und Unterarmschlägen

gegen die Tastatur (die berühmten tone clusters) sowie Saitenzupfen

bestanden; auf der amerikanischen Ostküste arbeitete dagegen

Charles Ives an seiner bekannten Concord Sonata (1914).

Es kommt so vor, als versuchten zur selben Zeit all diese Genies

wie moderne Alchemisten, aus dem Klavier Klangeffekte und -texturen

zu gewinnen, die bisher von der ‚offiziellen’ Musik

ignoriert worden waren.

Bela Bartók hatte seinerseits mit dem Instrumentarium des

Ethnomusikwissenschaftlers gearbeitet: Seine Reisen durch sein Vaterland

hatten ihm eine noch voll zu erforschende musikalische Welt offenbart:

Diese wies melodische und harmonische Besonderheiten auf, die Bartók

sich meisterhaft angeeignet hatte, wie er gerade in den Improvisationen

über ungarische Volkslieder (1920) zeigt. Hier taucht der typische

Liszt’sche Trick – mal zitiert, mal verarbeitet –

wieder auf, der darin besteht, ein bekanntes Motiv wiederaufzunehmen

und durch Notengirlanden, Arpeggien und Verzierungen zu schmücken

– dies fällt in Paraphrasen aus Opern, wie der berühmten

Paraphrase des Verdi’schen Rigoletto, besonders auf. In den

Improvisationen benutzt Bartók den Liszt’sche Trick

auf verschiedene Art und Weise – mit einem explosiven Effekt,

der gleichzeitig spröde, antisentimentalistisch und antirhetorisch

ist. So entzünden sich die kleinen Sekunden, die Debussy geschmeichelt

hatten, unverhüllt im fünften Stück und alternieren

dort mit den Quinten, die an ländliche Volksmusik erinnern;

im siebten Stück – das nicht zufällig als Hommage

auf Debussy für eine Gedenkausgabe der Revue Musical gewählt

wurde – kommt das Volksmotiv in den Klangtexturen vor, die

an La Cathédrale Engloutie erinnern, doch jeglicher luftigen

Suggestion entblößt sind.

Die erste Weltkrieg hatte die Welt der Mélisande und der

Monet’schen Seerosen begraben: Während der Franzose Debussy

in der blutigsten Phase des Kriegs gestorben war, hatte sein ungarischer

Kollege Bartók die nicht leichte Verpflichtung übernommen,

alles, was von der musikalischen Kultur seines Landes noch zu retten

war, der ganzen Welt zu schenken – dabei verzichtete er auf

eine manieristisch-kleinbürgerliche Volkstümelei, suchte

neue Anregungen zwischen Klang und Geräusch und bat sogar fünf

Jahre später Cowell darum, dessen tone clusters in seinen Kompositionen

verwenden zu dürfen.

In

der Welt um die Jahrhunderstwende, die ihrer eigenen Selbstmord

entgegentanzte, mochte ein Komponist wie Skriabin fehl am Platz

vorkommen – und das besonders im Vergleich zu seinem Studienkollegen

Rachmaninov, der als echter Salonlöwe jeder Situation gewachsen

war und sich in Virtuositäten und exotischen Kompositionstricks

schwelgte. Zugleich erscheint Skriabin jedoch viel moderner: Er

flirtet mit der Theosophie, stellt Theorien über musikalische

und visuelle Synästhesien aus Klängen, Farben, Tänzen,

Projektionen auf und nimmt die aktuelle postmodernistische Kontamination

praktisch schon vorweg – und das noch vor sieben Jahrzehnten.

Auch Skriabin wird mit dem (spät-)romantischen Klavierstil

fertig, der allmählich verarmt hatte, doch geht dabei mit Gogol’schen

Ironie vor: Das Prélude et Nocturne für die linke Hand

setzt sich zum Ziel, eine Welt aus schmachtenden Arpeggien, süßen

Melodien und leisen Akkorden zu schaffen, die aber, wenn sie mit

zwei Händen ausgeführt würden, sich als nichts besonders

originell erweisen könnten.

Skriabin will aber, dass eine einzige Hand, die linke, das ganze

Stück übernimmt – mit allen technischen Schwierigkeiten,

die dabei entstehen. Damit erzielt er eine rare Klangfülle

und eine Kraft, die alle für die Hervorhebung der Melodie nötigen

harmonischen Nuancen enthält.

Die

Reise wird natürlich weitergehen: Als nächste Etappen

gelten John Cages präpariertes Klavier, La Monte Youngs well

tuned piano, John Adams herzzerreißende und doch unmögliche

Aufstöberung einer verlorenen musikalischen Welt, oder –

im Jazz-Bereich – der Mix aus Afrikanismus und Modernismus

beim afroamerikanischen Virtuosen Cecil Taylor, der einen Musikhochschulabschluss

hat und die afrikanische Musik erforscht.

Alles, alles nahm jedoch hier seinen Anfang, als man begann, das

Klavier als ein Möbelstück zu betrachten, das das Prestige

derer, die es spielen bzw. besitzen, verstärkt, und es zu einer

ewigen Werkstatt für Erfindungen und Entdeckungen zu machen,

die sowohl vergangenheits- als auch zukunftsorientiert sind.

Francesco

Chiari

(Übersetzung:

AdrianoMurelli)

Un breve accenno

... del nuovo CD ... "buon ascolto"

| |

|

01. |

Prélude pour la main gauche op. 9 n. 1

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN

- Prélude et Nocturne pour la main gauche op. 9 -

2'41" |

| |

|

02. |

Nocturne pour la main gauche op. 9 n. 2

ALEXANDER SCRIABIN

- Prélude et Nocturne pour la main gauche op. 9 - 5'15" |

| |

|

03.

|

Brouillards

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

- Préludes. Libro secondo - 3'57" |

| |

|

04.

|

Feuilles mortes

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

- Préludes. Libro secondo - 3'06" |

| |

|

05.

|

La puerta del vino

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

- Préludes. Libro secondo - 3'26" |

| |

|

06.

|

Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

Préludes. Libro secondo - 3'20" |

| |

|

07.

|

Bruyères

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

- Préludes. Libro secondo - 3'28" |

| |

|

08.

|

Général Lavine, eccentric

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

- Préludes. Libro secondo - 2'50" |

| |

|

09. |

La terrasse des audiences du clair de lune

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

- Préludes. Libro secondo - 4'35" |

| |

|

10.

|

Ondine

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

- Préludes. Libro secondo - 3'57" |

| |

|

11.

|

11 Hommage à S.Pickwick, Esq., P.P.M.P.C.

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

- Préludes. Libro secondo - 2'31" |

| |

|

12. |

Canope

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

- Préludes. Libro secondo - 3'17" |

|

|

13. |

Les tierces alternées

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

- Préludes. Libro secondo - 3'07" |

|

|

14. |

Feux d’artifice

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

- Préludes. Libro secondo - 5'09" |

|

|

15. |

Molto

moderato

BELA BARTOK

- Improvisations sur des chansons paysannes hongroises op.20

- 1'09" |

|

|

16. |

Molto

capriccioso

BELA BARTOK

- Improvisations sur des chansons paysannes hongroises op.20

- 1'07" |

|

|

17. |

Lento,

rubato

BELA BARTOK

- Improvisations sur des chansons paysannes hongroises op.20

- 2'36" |

|

|

18. |

Allegretto

scherzando

BELA BARTOK

- Improvisations sur des chansons paysannes hongroises op.20

- 0'54" |

|

|

19. |

Allegro

molto

BELA BARTOK

- Improvisations sur des chansons paysannes hongroises op.20

- 1'05" |

|

|

20. |

Allegro

moderato, molto capriccioso

BELA BARTOK

- Improvisations sur des chansons paysannes hongroises op.20

- 1'41" |

|

|

21. |

Sostenuto,

rubato (à la memoire de Claude Debussy)

BELA BARTOK

- Improvisations sur des chansons paysannes hongroises op.20

- 2'02" |

| |

|

22. |

Allegro

BELA BARTOK

- Improvisations sur des chansons paysannes hongroises op.20-

2'00" |

Etichetta

LIRA CLASSICA

Catalogo N°LR

CD 120

Anno 2009 |

Prodotto

da Massimo Monti

Musicisti Associati Produzioni M.A.P.

Distribuzione

M.A.P. |

questo

prodotto è acquistabile al

prezzo di €uro

12,99

più spese di spedizione

(clicca qui) |

|

o

in alternativa direttamente sul

nostro sito MAP SHOP,

con

pagamento con

Carta di Credito

(clicca

qui) |

| |

|

|

|

|

| |